* I wrote this in December 2023, so although the principles remain the same, some elements may be out of date *

Linking the science of global climate change to targeted action in our personal and professional lives can be extremely hard. In the buildings sector, the multitude of broad ranging certifications (LEED, BREEAM, WELL etc) has made it almost impossible to identify a genuinely sustainable building; one that meets the needs of today without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

To avoid compromising humanity’s future we must limit global warming to within 2°C of pre-industrial levels, or even better to within 1.5°C, as per the 2015 Paris Agreement. We can therefore reasonably say that a building that doesn’t allow us to achieve this goal is not sustainable.

Although the climate science is extremely complex, one relatively simple output is a carbon budget. This is an amount of CO2e that the world can emit between now and 2050 in order to meet the requirements of the Paris Agreement.

The carbon budget covers the whole world, so needs to be shared by all sectors. Allocating an appropriate proportion of the budget to buildings should tell us how much carbon these assets can emit before tipping over into not-sustainable. The budget can be further divided into building operation (about 28% of global emissions) and construction (about 11% of global emissions). For the purpose of setting meaningful embodied carbon targets, the focus of this calculation is emissions from materials and construction, the 11%. The global budget can also be divided up and allocated to different countries.

In the UK our carbon budgets are set for each 5-year period between 2008 and 2050 with the help of the Climate Change Committee (CCC). Although these budgets have a firm basis in science, social and economic elements are also taken into account.

Time Period and Total UK Carbon Budgets

2023-2027 – 1,950 MtCO2e

2028-2032 – 1,725 MtCO2e

2033-2037 – 965 MtCO2e

Based on the historical data described above, it is reasonable to assume that 11% of this budget goes to construction. Around 3% will be for infrastructure, and around 3% for building repair, refurbishment and maintenance (based on the financial value of new-build versus existing building construction work in the UK). This leaves just under 5% of the total budget for new buildings’ upfront carbon. The limits step down every 5 years as we enter a new budgeting period.

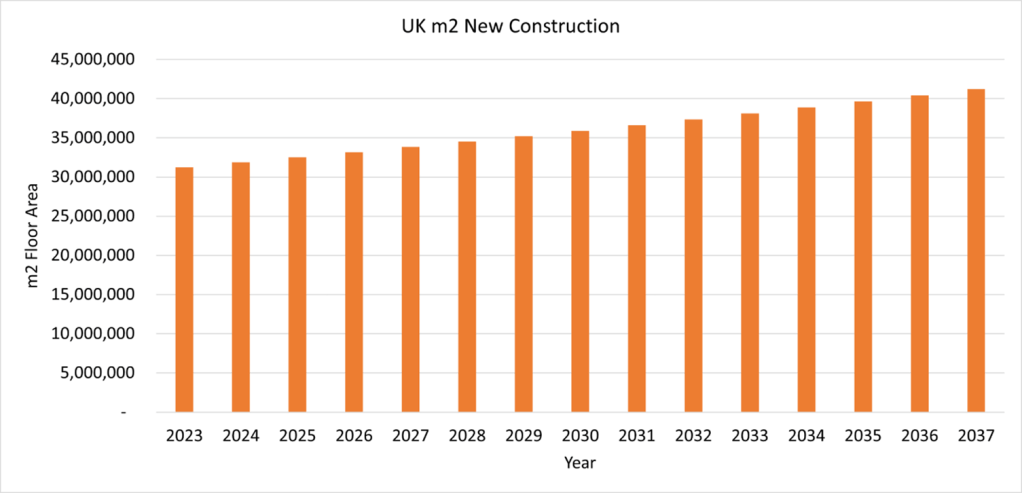

To convert this national upfront embodied carbon budget into a more understandable and applicable metric, we need to estimate the floor area of new buildings each year, in m2. This is possible by using ONS data for new construction value, and an average cost of new construction (£2,540/m2). We can also reasonably assume that construction volume will increase by a few percent each year.

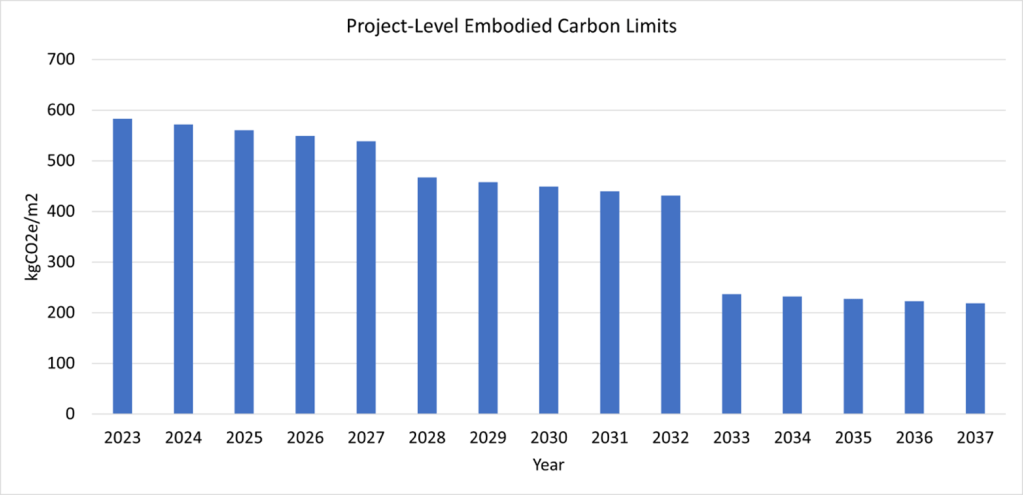

Dividing the carbon budget by the floor area gives an annual new building embodied carbon limit in kgCO2e/m2.

There is a slight decrease each year to account for an equal budget being divided by a gradually increasing floor area, in addition to bigger decreases every 5-year budgeting period. Taking the average for each period gives:

2023-2027 – 560 kgCO2e/m2

2028-2032 – 450 kgCO2e/m2

2033-2037 – 230 kgCO2e/m2

If a new building’s upfront embodied carbon exceeds this limiting value for the period during which it was constructed then it shouldn’t be described as sustainable.

These limits are eminently achievable, starting with around a band C of the LETI upfront embodied carbon targets and moving to an A+ by the 2030s. That said, any buildings which rely on the combination of concrete, steel and glazing will probably end up in the not-sustainable category (even if they’ve achieved BREEAM Very Very Good or LEED Platinum Jubilee).

Unsurprisingly, I’m not the first person to have gone through this process. The UKGBC’s Whole Life Carbon Net Zero Roadmap (2021) is based on a very similar logic, although omits the final step of converting the budget into clear and tangible per m2 targets. There may be good reason for this, but it makes the whole piece feel abstract and far removed from design.

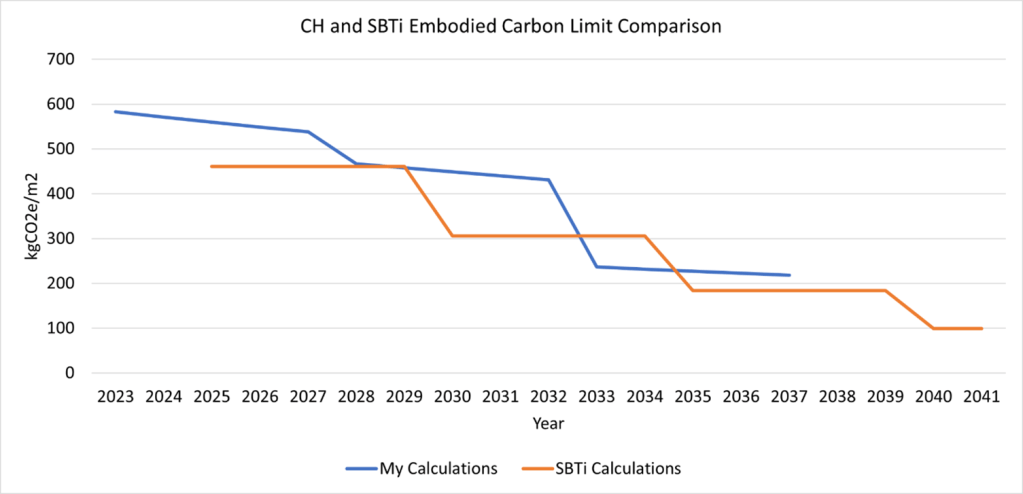

The clever people of Ramboll and Sweco have also calculated some 1.5°C embodied carbon pathways for the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), converting into kgCO2e/m2 and going a step further by producing different limits for different building types. I hadn’t read their draft paper before writing this (honestly), but now realise they have essentially done a more detailed job of my back-of-the-envelope calculations. By allocating the carbon budget based on historical global emissions proportions, I think I have inadvertently been “grandfathering”. It’s well worth reading their piece of work in detail, it doesn’t seem to have received the attention it deserves (link below).

Pleasingly for my own confidence, my figures are not far off those calculated for the SBTi. For ease of comparison, I have taken a weighted average across the building typologies defined by the SBTi approach.

The UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard is also planning to use a top-down approach to their target setting. I don’t know exactly what this will involve but assume it might be similar to all of the above, via various task groups, steering committees and dumas. It will be interesting to see what they produce, and how well it aligns with my figures and those of the SBTi.

In conclusion, it isn’t as complicated as it looks to set project-level upfront embodied carbon limits based on the scientific requirements to avoid catastrophic climate change. What’s more, the limits are well within reach if the industry can implement a shift away from the energy hungry architecture of the last 70 years. That’s a pretty big caveat.

We should start by putting a stop to the confusing sustainability messaging associated with certifications and “ESG”. If a project doesn’t come in under the limits described here, or more accurately by the SBTi, it probably isn’t sustainable. A similar approach can be applied to operational carbon and combined with the embodied carbon limits. Finally, it is worth explicitly saying that I have omitted the carbon budget for refurbishment or renovation, focusing only on new-builds. In practice, it may not be sensible to treat these categories separately. There is of course a strong argument to build less, and to use more of the new-build carbon budget for refurbishment.

Leave a comment